Still Flying Blind: Can Meteorologists Help Epidemiologists with Coronavirus?

Things are not going well these days regarding predicting the future of coronavirus in the U.S., with the epidemiological community, including critical government agencies, not succeeding in these important areas:

- They do not know the percentage of the U.S. population with active or past COVID-19 infections.

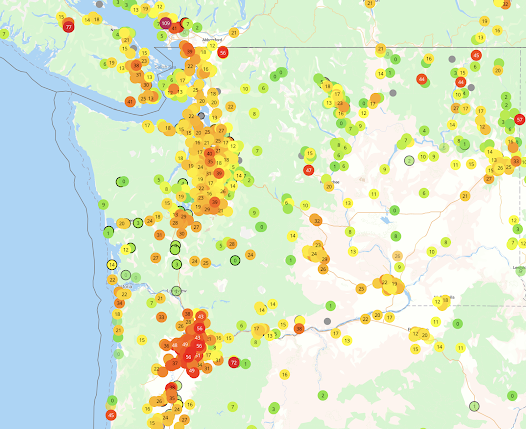

- They do not have the ability to quality control and combine virus testing information into a coherent picture of the current situation. This is a big-data problem.

- The epidemiological simulation models used by U.S government agencies or American universities have a poor track record in their predictions, with their quantification of uncertainty unreliable.

>media, social media, and several new research papers. The UW IHME model, often quoted by local and national political leaders, has been particularly problematic (this paper describes some of the issues), including the fact that its probability forecasts are highly uncalibrated. The UK Imperial Model in mid-March predicted 1.1-1.2 million deaths in the U.S., even with mitigation (so far the U.S. death toll has been about 60,000). Many of the coronavirus prediction efforts have evinced unstable forecasts, with great shifts as more data becomes available or the models are enhanced.

The poor performance of these models in predicting the coronavirus is not surprising: the lack of testing and particularly the lack of rational random sampling of the population results in no viable description of what is happening now. The favored IHME model is only based on death rates, not on the infection state of the community. Can you imagine if meteorologists tried to predict weather only using data around active storms? Very quickly, the forecasts--even of storms--would become worthless. The same happens with coronavirus.

You cannot skillfully predict the future if you don't have a realistic starting point. Furthermore, some of the models are highly simplistic and not based on the fundamental dynamics of disease spread (like the curve-fitting IHME approach).

You cannot skillfully predict the future if you don't have a realistic starting point. Furthermore, some of the models are highly simplistic and not based on the fundamental dynamics of disease spread (like the curve-fitting IHME approach).

The U.S. has a permanent, large, well-funded governmental prediction enterprise for weather prediction, one that has improved dramatically over the past decades. No such parallel effort exists in the government for epidemiological modeling. Instead, University groups, such as UW IHME, have revved up ad-hoc efforts using research models.

The Bottom Line:

Our government and political leadership have been making extraordinary decisions to close down major sectors of the economy, promulgating stay-at-home orders, moving education online, and spending trillions of dollars.

And they have done so with inadequate information. Decision makers don't know how many people are infected or were infected. They don't know how many people are already immune or the percentage of infected that are asymptomatic. They are using untested models that have not been shown to be reliable. This is not science-based decision making, no matter how often this term has been used, and responsibility for this sorry state of affairs is found on both the Federal and state levels.

And they have done so with inadequate information. Decision makers don't know how many people are infected or were infected. They don't know how many people are already immune or the percentage of infected that are asymptomatic. They are using untested models that have not been shown to be reliable. This is not science-based decision making, no matter how often this term has been used, and responsibility for this sorry state of affairs is found on both the Federal and state levels.

The meteorological community has a long and successful track record in an analogous enterprise, showing the importance of massive data collection to describe the environment you wish to predict, the value of sophisticated and well-tested models to make the prediction, and the necessity to maintain a dedicated governmental group that is responsible for state-of-science prediction.

Perhaps this approach should be considered by the infectious disease community. and the experience of the numerical weather prediction community might be useful.

Perhaps this approach should be considered by the infectious disease community. and the experience of the numerical weather prediction community might be useful.

Comments

Post a Comment