Thunderstorms in western Washington are a wimpy lot.

Infrequent and weak, they rarely get above 15,000 ft, unlike their vigorous cousins over the central and eastern U.S.

The reason for their weakness? Mainly the cool water of the eastern Pacific, which lessens the warmth at low levels and the water vapor content available in our region compared to the thunderstorms over the eastern half of the nation.

When thunderstorms are vigorous and strong they can rise high enough to reach the stratosphere, where warming conditions and dry air act as a barrier to thunderstorms' upward penetration.

And when they hit this barrier, typically 25,000 to 35,000 feet above the surface, the thunderstorm clouds tend to spread out in what is known as the anvil (see pictures below). From the first picture, you can see why it is called an anvil, a familiar item of the blacksmith's trade.

Now we rarely see anvils in western Washington, so you can imagine my delight when I walked outside yesterday (Tuesday) around 6 PM at the NOAA facility in NE Seattle and looked up (see imagery). A beautiful thunderstorm with a well-defined anvil!

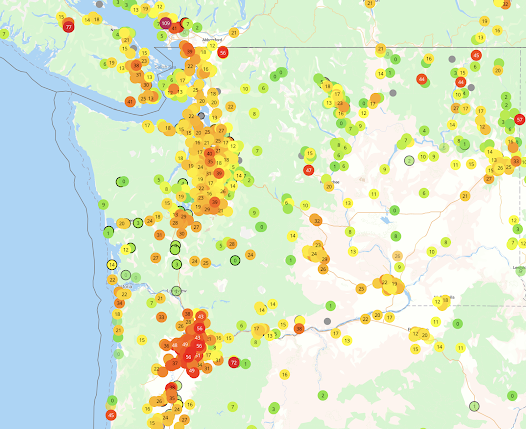

The thunderstorm was very evident in the weather radar at this time, as shown by the radar image at 5:51 PM (left panel), with the associated heavy precipitation (reddish colors) just northeast of Everett (my location shown by a blue circle).

The radar can also tell us the top of the radar echo. I was shocked by the value, shown in the right panel: 26,000 ft. Wow.

The visible satellite image at this time clearly shows the big cumulonimbus cell (see below--I put a dashed oval around the thunderstorm)

There were several lightning strikes associated with this thunderstorm.

Was this thunderstorm entering the stratosphere?

To determine the height of the boundary between the troposphere (the lowest layer of the atmosphere) and the stratosphere, also known as the tropopause, we can examine the vertical temperature and moisture sounding at Forks, on the WA coast, valid at 5 PM Tuesday (see below).

Temperature is the red line and dew point is the blue dashed line. Temperature generally decreases in the troposphere and stops declining and eventually warms in the stratosphere (due to heating of the ozone layer by the sun). Moisture drops in the stratosphere (the dew point drops precipitously).

The locations of the tropopause in this sounding is very clear and indicated by the red arrow: about 7300 meters (or 24,000 ft). Actually quite a low stratosphere height.

So our energetic thunderstorm had enough meteorological "oomph" to push into the stratosphere....something known as an overshooting top.

And here is a marvelous video of the anvil pushing northward, from a viewpoint on the north Kitsap Peninsula (Skunk Bay Weather website).

An unusually tall thunderstorm for around here with a very nice anvil.

And if you ever want to see the best anvil picture for the region of all time, check out this amazing image by

professional photographer Frank Jenkins. Visual poetry. He kindly allowed me to use this image in my Northwest weather book.

_____________________________________

Before you renew support for Public Radio Station KNKX please read this.

Comments

Post a Comment