The Daily Cycle of Coastal Low Clouds and Flowing Fog

During the middle to late spring, the northeastern Pacific fills will low clouds, as illustrated by the visible satellite image from two days ago (shown below).

And during fair-weather periods, as we have experienced during the past week, there is a daily rhythm of clouds along the coastal zone east of the Cascade crest, with clouds pushing in overnight and burning back during the day.

Consider what has happened during the past day.

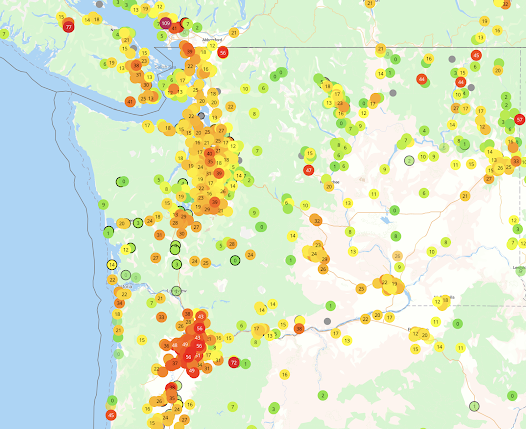

Last night at 5 PM, there were lots of low clouds along the coast and a tendril of stratus/fog extending into the Strait of Juan de Fuca

Central Puget Sound was fog free this morning as were the western slopes of the Cascades.

By noon, the low clouds had pulled back to the coast

This cycle of nighttime influx and daytime retreat has been going on for days.

You, of course, are asking why.

One reason is that the pressure difference between the coast and inland varies over the day.

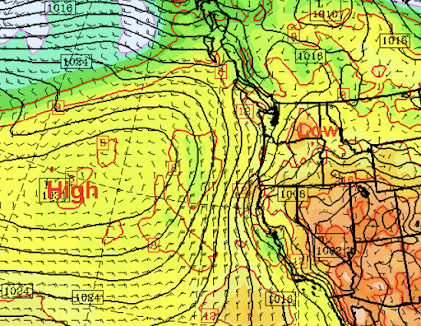

The general pressure pattern over the region for the past week has been high pressure offshore and lower pressure inland (see sea level map for 5 AM on Friday). The lines on the map are isobars of constant pressure, and you can see the high pressure offshore and lower pressure east of the Cascade crest. This pressure pattern (high pressure offshore, low pressure inland) tends to produce northwesterly winds along the coast, with a weak onshore component of the low-level winds.

This pressure pattern tends to push the offshore stratus/fog inland across western Washington. But the pressure pattern is modulated over time, with warming inland tending to cause the pressure to fall, which produces a stronger onshore pressure difference (higher pressure offshore, lower pressure inland). This increases the onshore (westerly) winds at low levels, which help to bring in low clouds.

Want proof? Here is a plot of the difference in pressure between Hoquiam on the coast and Seattle. Positive values mean Hoquiam has higher pressure. The daily heating caused the onshore pressure difference to increase during the afternoon and early evening to about 1.9 hPa (hPa is a unit of pressure) around 10 PM. This helped push the stratus in. Nighttime cooling over land caused the difference to decrease rapidly overnight. Then heating today resulted in the onshore pressure difference (or gradient) increasing during the day, which will cause the stratus to push in again tonight.

The wind effects are not the only mechanisms for the diurnal (daily) changes in low clouds.

Heating during the day causes vertical mixing that helps destroy low clouds from its edges.

Keep in mind that the low clouds are quite shallow, something that is evident from the view of the low clouds from the Seattle panocam this morning around 9 AM. Note that the tongue of the stratus barely made the entrance to Elliott Bay.

A few days ago, the tongue of morning status got a bit further south and crested over portions of West Seattle. Here is an extraordinary video taken by Michael Snyder of what happened. Quite beautiful. It looks like water pushing a boulder.

Comments

Post a Comment