Is California Experiencing More Weather Whiplash?

---John Steinbeck, East of Eden

___________________________________________________________

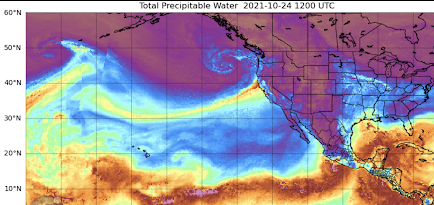

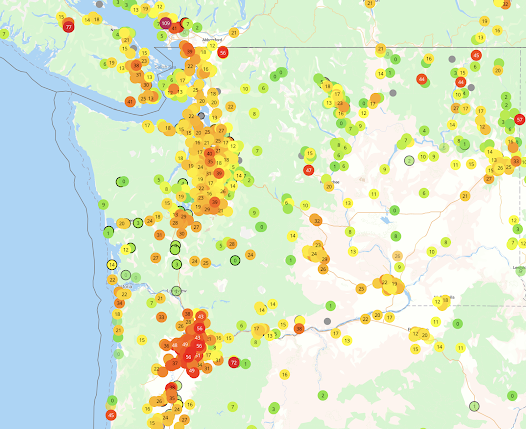

After the heavy rains of the past few days over central and northern California, a number of media outlets are talking about California suffering from "Weather Whiplash", since the record precipitation this autumn follows a year of drier than normal conditions.

And several media outlets are going much further, claiming the the "whiplash" is the result of climate change and is worsening over time (see below). Such articles quote from scientists whose research suggested increasing whiplash based on their examination of climate model projections.Well, what is the truth?

Global warming has been significant for several decades so we should see evidence of increasing "whiplash" if climate change is a major forcing mechanism. Strangely, none of the handful of studies in the scientific literature on whiplash has looked at the observational record. Just the climate models.

But in this blog, the analysis will be done!

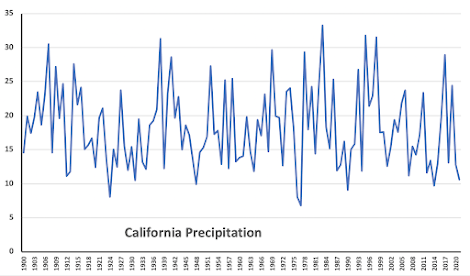

Let's examine the NOAA/NWS climate division data for California, and specifically, the precipitation for California's wet season of November through March from 1900 through 2021 (see below).

One is struck by several things.

There is really not much trend in California's winter precipitation.

And there is a lot of up and down variability---yes, weather whiplash. But there does not seem to be any long-term trend for more or less precipitation whiplash.

To illustrate this point, let's plot the yearly whiplash...a WHIPLASH INDEX.. by simply taking the difference between each year's and the previous year's winter precipitation for California. Since we don't care which way the whiplash goes (wet to dry or dry to wet), I will plot the absolute value of the difference. I also plotted (red dots), a 10-year moving average to smooth out the variation over time (see below).

Really very little long-term trend in California precipitation whiplash, with the worst of it from roughly 1975 to 1997.

Will whiplash get worse in the future?

I am involved in regional climate simulations, using an ensemble of high-resolution projections driven by an ensemble of many global climate models. This is the gold standard for such work. We ran these simulations using the highly aggressive RCP 8.5 scenario for increasing greenhouse gases, which is certainly not realistic since it assumes that mankind keeps on burning increasing amounts of coal, among other things.

Below are the results for Red Bluff in northern California (winter precipitation) through 2100, with the green lines being the average of the many forecasts. During the end of the century, there is perhaps some suggestion of occasionally larger whiplash, but also extended periods of less whiplash. But again, the amount of CO2 emissions is undoubtedly too large.

I think the jury is still out on whether California whiplash will increase significantly during the second half of this century. And the research studies that have suggested big increases during this century also predicted major whiplash increases during the past two decades. These have not verified with observations.

Comments

Post a Comment