This Wedneday, October 12, marks the 60th anniversary of the extraordinary Columbus Day Storm, the most intense, damaging storm to hit the Pacific Northwest during the last century.

This blog will tell its story, describe the extreme winds and damage, tell you about the quality of the forecasts, and even examine whether global warming will change the frequency of such storms.

Note: I will be giving an online public talk on the big blow if you are interested (details later).

The steeple of Campbell Hall in Monmouth, Oregon

The extreme nature of the storm is hard to exaggerate.

It spread destruction from northern California to British Columbia, with winds exceeding 100 mph in many locations and over 130 mph in several locations.

It was a storm equivalent in strength to a category 3 hurricane. But bigger.

46 people died and 317 required hospitalization. Power was taken out for nearly the whole region. Millions of trees were toppled. Flooding occurred in California. If it hit today, it would easily cause tens of billions of dollars in damage.

A bronze statue called "Circuit Rider" was toppled by winds in Salem.

Although not a hurricane when it hit the Northwest (because it was not a tropical storm), the Columbus Day Storm started as Typhoon Frieda in the western Pacific. This tropical storm then moved northward, transformed into a midlatitude storm driven by differences in temperature (also known as a midlatitude cyclone), and then swung northward into our region on October 12 (see map below).

Several of the most intense storms hitting the Northwest have started as typhoons: many appear to retain some of the inner core intensity and substantial surrounding moisture of their tropical origins.Now, let's look at some surface weather maps during the storm's landfalling final day (the maps show sea level pressure).

At 4 PM the day before, the Columbus Day (CD) storm was due west of central California, while another (quite powerful) storm was offshore of our region. Parenthetically, many of our great storms have siblings that move through the days before and after.

By 10 AM on October 12th, the CD storm had revved up into a monster (with a central pressure around 960 hPa), bringing intense rain to California and hurricane-force gusts to the northern CA and southern OR coasts.

By 10 PM, the intense low was crossing the northwest tip of the Olympic Peninsula. Extreme winds were hitting western Washington at this time.

When the storm was of Oregon, its lowest pressure was around 955 hPa; most years our deepest storm is only around 980 hPa.

Equivalent to the central pressure of a category 3 hurricane:

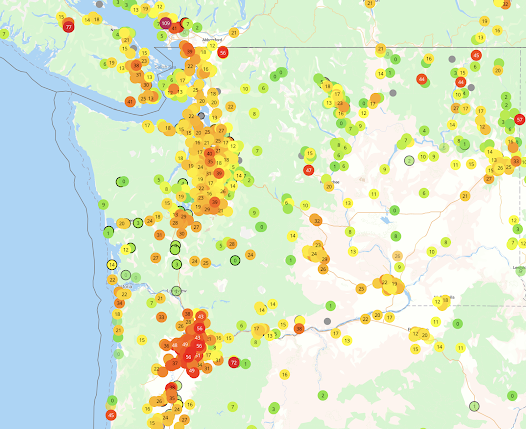

The maximum winds during the storm are shown below, courtesy of Dr. Wolf Read. Gusts to around mph in Renton and Bellingham. 116 mph in Portland, 127 mph in Corvallis and over 135 mph on the coast.

At Pt. Blanco, on the central Oregon coast, the winds got to 150 mph sustained, with gusts to 179 mph, before the anemometer disintegrated.

The Forecast

This intense storm was poorly predicted the day before.

As proof, here is a page from the Seattle Times on October 11th, which noted a partly cloudy day forecast in the interior and gale-force winds along the coast. Forecasters expected a minor coastal blow, but nothing like the hurricane-force winds that hit the entire region.

It is easy to understand why the forecasts were problematic that day.

These were the days before weather satellites when meteorologists only received a few scattered ship reports over the Pacific. Only during the final morning were there enough coastal reports to suggest a mega-storm was approaching.

Here is the actual surface chart produced by some forecasters at the Portland Weather Bureau office at 5 AM on October 12

As you may know, I do weather and climate modeling/prediction as part of my day job, and I asked two of my staff (Rick Steed and David Ovens) to rerun the forecast for the Columbus Day storm using a modern prediction system and at high resolution. Computer forecast models were primitive in those ancient days--could we do better with modern tools?

The results are shown below. We were able to get an impressive storm, but not nearly as intense as the real thing (which was about 20 hPa deeper) and with a track too far eastward compared to the real thing.

Our deficient results are not surprising: without weather satellites and other modern observing systems over the ocean, there were not enough data to properly describe weather conditions over the Pacific. Even more weather prediction models can not forecast weather skillfully without sufficient data to start with.

Has Global Warming Intensified Major West Coast Storms? Will it?

The answer appears to be no.

First, since global warming has been going on for several decades, we should already note some impact on storm strength---if a connection exists.

Below are the maximum winds each year in Seattle and Portland during the past half-century or so. There is no evidence that winds are increasing...in fact, it looks like a slight decrease has occurred.

This trend is consistent with the observation that we haven't had a big Pacific windstorm in a while, with the last major event being the 2006 Hanukah Eve storm.

Finally, in 2015 the UW Climate Impacts group completed a study that examined regional climate model projections to determine whether global warming would increase the maximum winds of the region. This study, of which I was one author, found no increase in maximum winds for the region as the planet warmed.

Number of times per year winds hit a high-wind threshold

over the region. No trend

There are reasons why strong Pacific storms are not increasing, including the reduction of horizontal temperature gradient under global warming.

Not all weather becomes more extreme as the earth warms slowly, something that may surprise after the relentless hype in the media.

My Talk on the Storm on Wednesday

I will be giving a presentation on the Columbus Day event on Wednesday at the department's Dynamics/Climate seminar at 3:30 PM (zoom information: https://washington.zoom.us/j/99470540010)

And I recently gave a talk on the storm at the Oregon Chapter of the American Meteorological Society (found here). I was joined by Professor Wolf Read of Simon Fraser University.

Comments

Post a Comment