Was Global Warming Behind the Recent Smoky Period in Western Washington?

Some media outlets and activists have been making big claims that the recent westside wildfires and resultant smoke were the result of global warming (also known as "climate change").

Imagine if you were a journalist assigned to write a story on the potential connection between global warming and westside wildfires. You would certainly want to ask these questions:

1. Is the area burned west of the Cascade crest increasing over time? If global warming was the cause one would expect a trend towards more westside wildfires over the past few decades when warming has been greatest.

2. Are the meteorological factors associated with westside fires trending up over the past decades? Furthermore, do climate model projections indicate increases over time in these key parameters?

In the case of westside fires, the key parameter is strong easterly (from the east) winds. All major westside fires are associated with such winds. Another (secondary) factor is a dry late summer and autumn, the season of virtually all westside fires.

The Yacolt Burn in 1902 was the most extensive westside fire during the past 120 years.

Let's look at the facts.

Is there a trend in westside wildfires?

Below is a plot of the burned acreage west of the Cascade crest in Washington. There were BIG fires early in the 20th century (Yacolt, 1902; Dole Valley, 1929). Then there was virtually nothing until the much smaller 1951 Olympic Peninsula Fire. Then another fire "drought" until another small fire in the Olympics (the 2015 Paradise fire), followed the modest fires of this year.

Do you see evidence of a trend towards more westside fires in Washington? I don't. And that alone is enough to deflate any claims of greenhouse warming revving up westside fires.

The Essential Meteorological Requirments for Westside Fires

Westside forests are generally not prone to large fires. The reasons are evident: these are relatively moist environments, experiencing huge precipitation totals on the windward slopes during the cool season. They are characterized by a green, moist canopy.

The period from June to September has little rain in a normal year and there is a slow drying of the surface during the summer, as well as the melting of the snowpack at middle and higher elevations. During the summer there is that generally onshore flow from off the Pacific that keeps temperatures moderate and the air relatively moist. An inhospitable environment for westside fire.

As long as the flow is westerly (from the west) there is little chance of major westside wildfires. Thus, the ESSENTIAL ingredient for westside fires is to have STRONG easterly winds.

Repeat that statement 3 times. It is that important.

Easterly winds encourage western wildfires in several ways. First, it replaces the cool, moist ocean air with very dry, warm air from east of the Cascade crest. Relative humidities can decline from 50-80% to under 10%. Dry conditions are good for fire, helping to rapidly dry surface fuels--which makes them much more flammable.

Second, as the easterly flow descends the western slopes of the Cascades it is warmed by compression, driving humidity even lower. Very warm, dry air on the slopes enhances fire potential.

Third, strong winds can provide more oxygen to fires (which they need) and can blow hot embers ahead of the fires, enabling them to spread more quickly.

Fourth, strong easterly winds can START fires, such as by downing powerlines or pushing branches onto powerlines.

I have a National Science Foundation project to look at westside wildfires in Washington and northern Oregon and I (and my students) have studied EVERY large westside fire. EVERY ONE OF THEM was associated with strong easterly winds.

With this key knowledge in mind, what will global warming do to strong easterly winds in our region?

The answer: global warming (a.k.a. climate change) will WEAKEN the easterly winds, working AGAINST more fires.

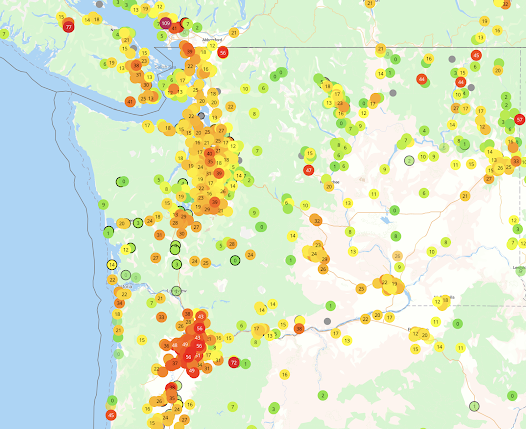

To reach this conclusion, we have applied an ensemble of many regional, high-resolution climate simulations. As illustrated by the figure below (which is from a peer-reviewed paper), increasing greenhouse gases (like CO2) result in weaker easterly winds (in this case near the crest of the central Washington Cascades).

Number of days with strong easterly winds from 1970 to 2100, based on high-resolution climate model projections

The reduction of strong easterly winds with global warming makes total sense physically.

Global warming preferentially warms the interior of the continent compared to the slow-to-warm coastal zone. Warming contributes to preferential pressure declines over the interior. Strong easterly flow is associated with higher pressure over the interior compared to the coast, and thus the preferential warming in the interior WEAKENS the easterly flow.

So the best science, from modeling to physical reasoning, indicates that wildfire-driving easterly flow WEAKENS under climate change. The opposite of the suggestions in the Seattle Times and elsewhere.

Are Autumns Getting Drier?

Although easterly winds are the critical requirement for westside wildfires, dry conditions are clearly helpful. Westside wildfires have occurred during periods of normal precipitation when the easterly flow was sufficiently strong and sustained, but prior dry conditions shorten the period required to dry the surface fuels. This year was extraordinarily dry--the driest summer/early fall on record-- and this allowed the strong easterly winds of last week to quickly enhance preexisting fires and initiate new ones.

So let's get to the essential question: is late summer/early fall precipitation declining on the western slopes of the Cascades and in western Washington in general?

The answer is NO.

Here is a plot of August to October precipitation for the last century for the western slopes of the Cascades (and eastern slopes of the Olympics) taken from NOAA Climate Division dataset. There is no long-term drying--if anything precipitation is going up a bit. Plotting other areas or individual stations in western Washington produces the same upward trend.

What do climate models project for the future of autumn precipitation as the Earth warms? As shown below, an INCREASE in precipitation.

The Bottom Line

In contrast to the claims of the Seattle Times and some activist types, there is no reason to expect future increases in the size or frequencies of westside wildfires. There is no observed upward trend in wildfire acreage west of the Cascade crest. Global warming should weaken strong easterly flow, the key meteorological factor associated with autumn westside wildfires. Furthermore, there is no evidence for decreased autumn precipitation over the region and climate models suggest that such precipitation should, in fact, increase.

____________

Comments

Post a Comment